Il mio Verdi , My Verdi

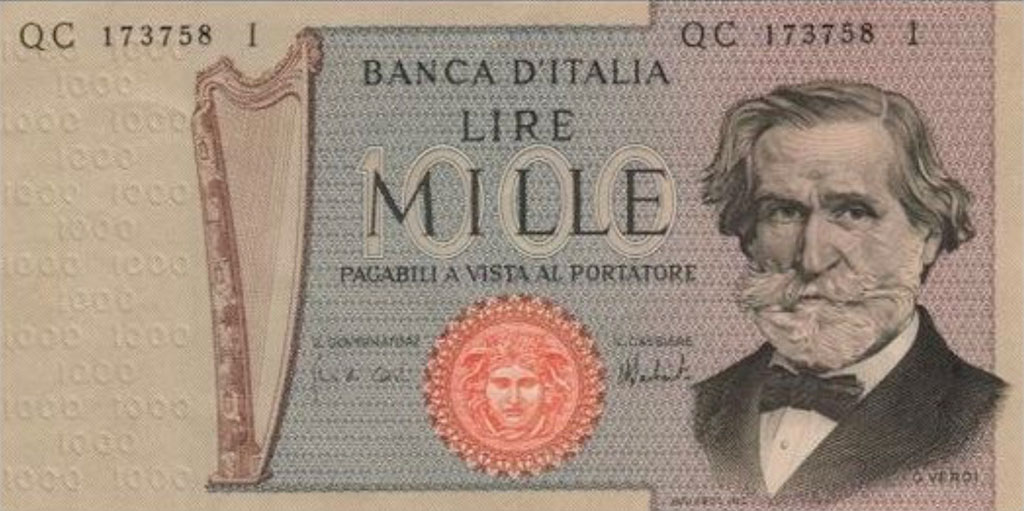

When I visited Italy for the first time as a 16 year old student, my love for the “most beautiful country in the world” began long before my career as an internationally touring opera singer, which later took me back there often. Since Italy at that time suffered from a total lack of coinage – this was shipped wisely to Japan – every caffè al banco, every postcard was bought with a 1000 lire bill.

And there, in his home country, I saw him for the first time: Giuseppe Verdi.

Of course I knew his music a little, but it was only when I studied singing at the Conservatory in Cologne that his work, his life and the great nineteenth century in which he lived opened up to me. Then, as a young student, I had the good fortune to visit him in his homeland, Emilia Romagna: Parma, Busseto, Le Roncole and above all, his villa “Sant’Agata”, where he retired as a world star at a relatively young age.

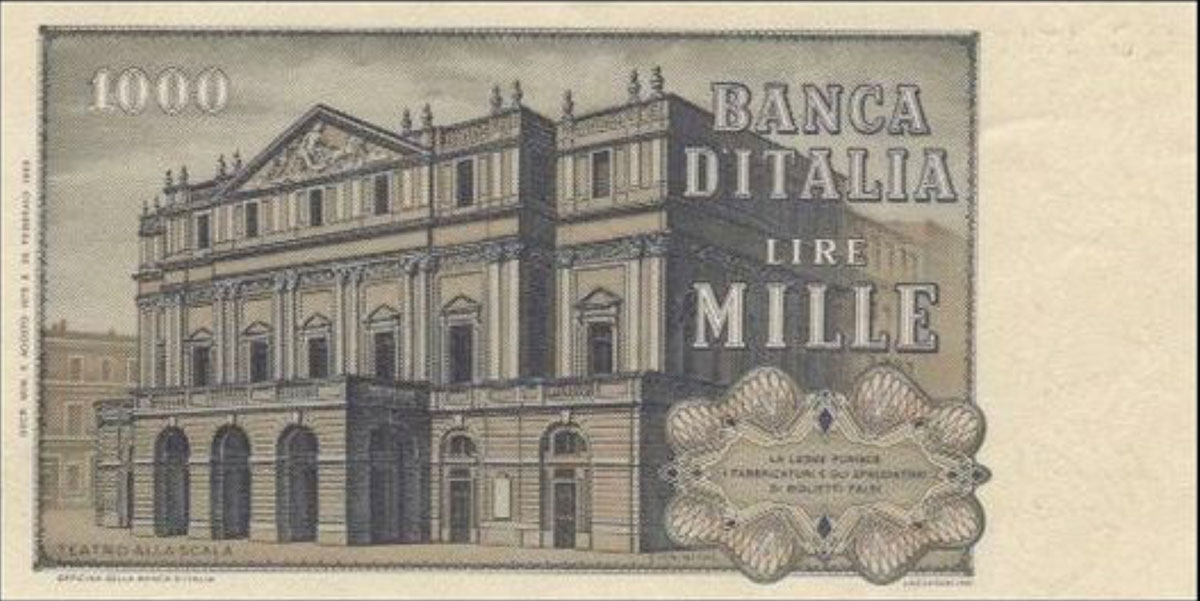

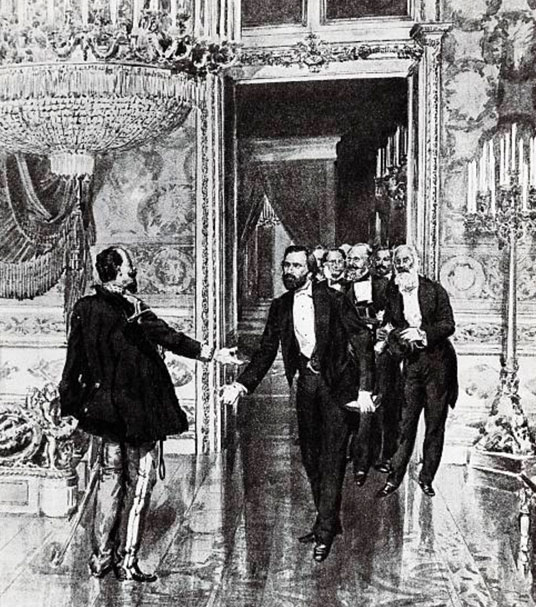

One of the highlights of my career was my performances at La Scala di Milano, Verdi’s artistic home. What a temple of vocal art and of the great romantic repertoire of the 19th century La Scala is!

And that’s where I remembered my old 1000 lire bill, on the back of which was written:

Io sono un contadino, I am a farmer

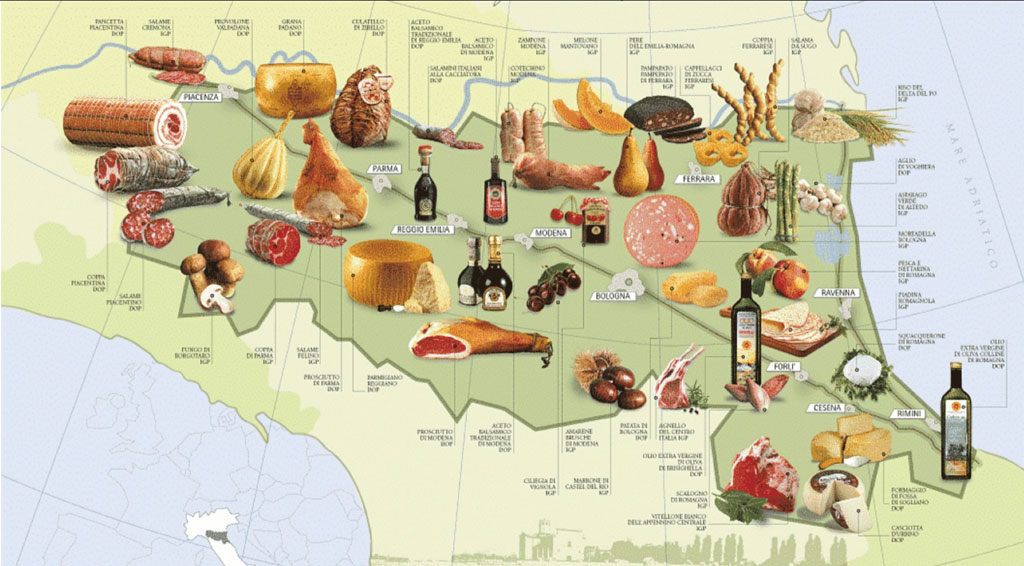

“Io sono un contadino” was his credo, and with the income from his operas he bought a patch of land in his homeland.

So it happened that most of the things on the table of the Villa of Sant’Agata came from his fields, produced by his farmers. Today one would refer to him as organically self-sufficient.

The most famous of products, the Parmiggiano Reggiano di Montagna (Parmesan cheese) and the Culatello di Zimbello (the best quality Parma ham) I had been able to taste myself in the farms that once supplied Maestro Verdi.

But the other dishes created by him, like the Tagliatelle alla Verdi, the Risotto alla Verdi and the Tournedos alla Verdi speak his down-to-earth language, like his music and his unbelievably beautiful melodies, which still hold the world in thrall today.

Il compositore. The composer

“Every music has its heaven” said Verdi, and set love as the central theme in the centre of his operas: the love of spouses, the love of parents, the love of La Patria, the love of his fatherland (in Italian it is characteristically referred to as the motherland).

He was also concerned with earthly things such as love, hatred, jealousy and patriotism, in contrast to the other great epitome of romantic opera, Wagner, who placed the theme of redemption at the centre of his work.

Toscanini once said that in the time of the love affair between Tristan and Isolde, the Italian couple had already fathered several children.

Who does not know the Triumphal March from Aida, the Prisoners’ Chorus from Nabucco, “la Donna è mobile” from Rigoletto, or the “Brindisi” from La Traviata to name just some of Verdi’s mesmerising and lasting legacy that conquered the world.

During your evening I will introduce you to the intoxicating beauty, human depth and power of some of Verdi’s operas – let yourself be surprised …

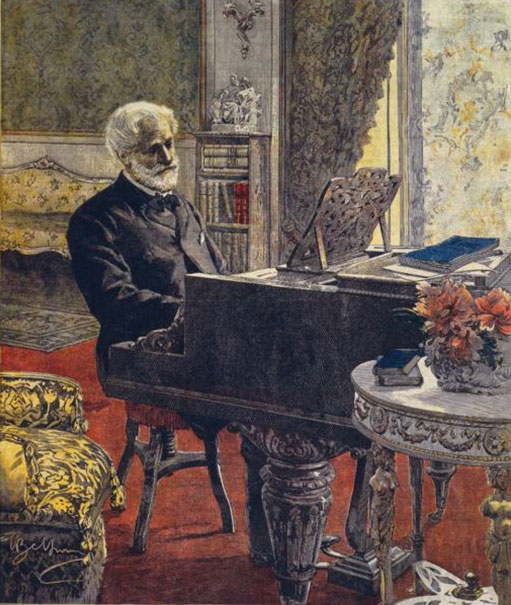

Here’s a small example of how Verdi, at the ripe old age of 78, was still writing overwhelmingly powerful music.

Il Patriota, the Patriot

Giuseppe Verdi (1813 – 1901) was also a prominent political figure in the history of nineteenth century Italy, the century of the Resorgimento, the unification of Italy that finally came about in 1861. It was his music that expressed and inspired the desire of Italians for a united “patria” in a grandiose fashion: “Va pensiero sull’ali dorate” from his Nabucco became a battle song, the secret national anthem of Italy.

„VIVA V. E. R. D. I.“

was graffitied on walls all over Italy as a slogan denouncing the foreign occupiers, since admiration for a composer did not provoke a political response.

But in fact this slogan stood for the man who became the first king of a united Italy:

Viva

V.ittorio E.manuel R.e D´ I.talia

Even today, Verdi’s music embodies the ethos of Italy’s secret national anthem, as evidenced by the solemn act of state in 2011 to mark the 150th anniversary of Italian unification in 1861:

Gala performance/act of state at Rome Opera, Prisoners’ Chorus from Nabucco conducted by R. Muti.

L’Umanista, The Humanist

When Verdi was once asked which of his works was the most meaningful to him, he answered: “la Casa di Riposo per Musicisti”, the retirement home for musicians in Milan.

Verdi donated the building and covered the cost of its maintenance, which to this day is paid from the royalties earned from his operas.

Even today, old musicians and singers find a dignified home in the Casa di Riposo, which is beautifully described in the Arte documentary Il Bacio di Tosca:

La Fine, the end

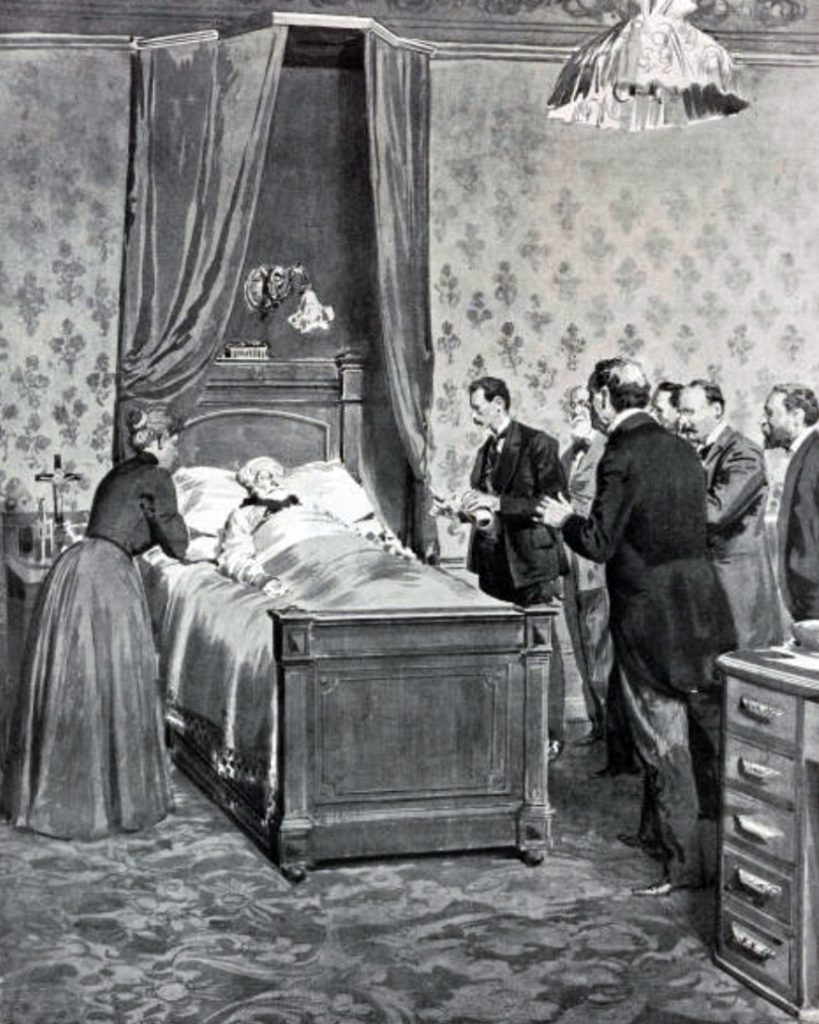

Verdi, the great artist, patriot and humanist, died in Milan on January 27, 1901 at the ripe old age of 88.

His funeral procession, attended by hundreds of thousands of people in Milan and 900 choristers singing the “Va pensiero” from Nabucco under the baton of Arturo Toscanini, eclipsed that of kings.

Funeral procession

At the end of his life Verdi was very lonely because he had outlived his wife, Giusseppina Strepponi, and most of his friends.

Perhaps he felt his peaceful death to be a redemption for the music that played in his inner ear:

R. Tebaldi with the “Ave Maria” from Act 4 of Otello Renata Tebaldi: Verdi – Otello, ‘Ave Maria’

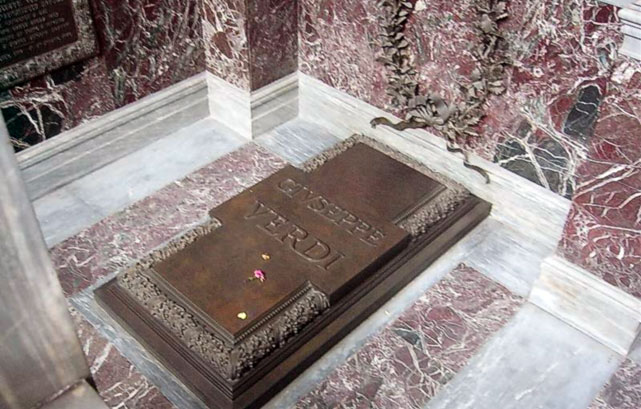

Verdi found his final, humble resting place in his Casa di Riposo in Milano.

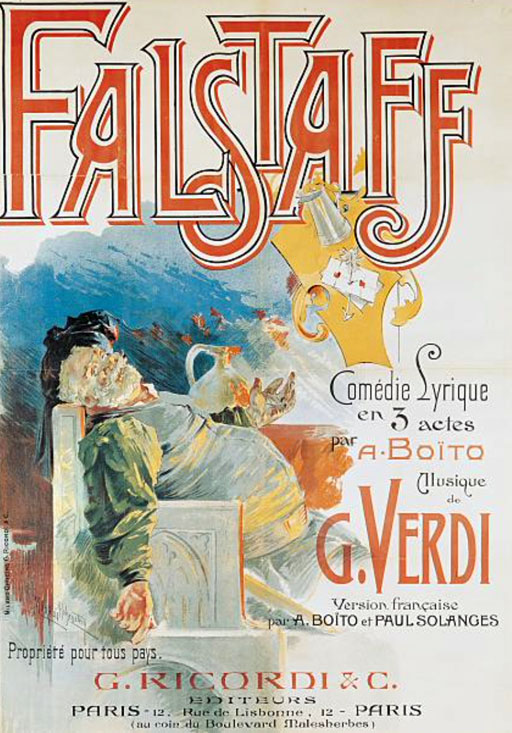

Unlike his musical opposite Wagner, who finished his artistic career with the “stage consecration play” of Parsifal and the words “Redemption to the Redeemer”, Verdi ended his work with a Shakespearean comedy, Falstaff.

And although there is always one person dead or dying in his operas, his last words as an artist were:

„Tutto nella vita è burla“

… everything in life is fun.

Bravo Maestro Verdi !